With Thanks to 12352 Chris “chwylms” Willmes

The primary purpose of recruit term at the colleges was pretty straightforward — in the shortest possible time, take a large group of boisterous young men from all across the country, all high school graduates, but with otherwise disparate backgrounds, and inculcate them with military culture and discipline, and in particular, the sub-culture and discipline of the military colleges. The lion’s share of this task was assigned to a select group of senior cadets; at Royal Roads, most of those senior cadets had been recruits themselves just twelve months earlier. (In the fall of ‘75, Royal Roads was in transition from a two-year to four-year, degree-granting institution, and so there was also a smattering of third-year cadets, who held the most senior appointments in the cadet wing, but there were no fourth year cadets.) Our barmen had to teach us close-order drill, how to care for our kit, how to wear it properly, housekeeping, the myriad of rules and regulations that comprised CADWINS, teamwork, table manners, even, but most importantly, discipline, especially to follow (lawful) orders, without hesitation, question, or complaint. The objective was to mould an unruly mob of teenagers into a cohesive, disciplined, junior term of cadets.

This objective our barmen achieved mostly by means of the time-honoured methods of operant conditioning, i.e., carrot and stick (mostly stick) that had been employed to great effect by the military forces of the world for centuries, long before some nineteenth-century psychologist coined the term, “operant conditioning.”

Our barmen occasionally paired this behaviour-modifying technique with another tool in their psychological toolbox, namely, classical, or respondent conditioning. (Think back to that MLM lecture on the topic of Pavlov and his salivating dogs.)

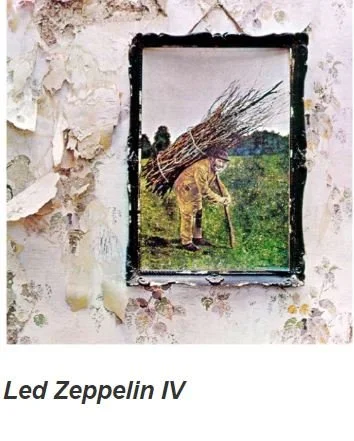

Every flight in the Wing had its own “wake up” song that was played by its CFL or DCFL at reveille. In Lasalle Flight, to rouse us from our slumbers, they would play Led Zeppelin’s “Black Dog”, with the volume of the stereo turned up to eleven (anticipating Spinal Tap by a decade). The pile-driving riff would launch even the most somnolent rook off of his pit (we didn’t sleep in them), shave, dress, square off the cabin, then rush downstairs to the foyer of Nixon Block, out the main doors onto the circle, and start doubling smartly across to Grant Block. Ensuring that the cabin was ready for inspection was probably the most exacting and time-consuming part of our early-morning routine. Textbooks had to be arranged in the bookcase in descending order of height, the windows opened precisely the length of a bayonet handle, the pillows on the bunks ironed smooth, the bedding pulled so tight you could bounce a quarter off of it, every sock in the bureau’s top drawer properly rolled and in its appointed place, the sink and mirror spotless, the linoleum floor swept, not a speck of dust anywhere, etc., etc. Our CFL would let us know that time was running out by playing “Black Dog” a second time; we knew that by the time the song ended, we had to be out of Nixon Block, or there would be consequences. Dire consequences.

Before coming to Royal Roads, I had been only vaguely aware of the band Led Zeppelin, and was pretty much ambivalent towards their music. That changed literally overnight; our CFL was a serious Led head, and he would play “Stairway to Heaven” every evening at lights out, to lull us to sleep (not that we needed a lullaby). I quickly learned to both fear and loathe “Black Dog.” I can still hear our CSTO bellowing, “panic, rooks!” as we rushed to get ready and get out. As rook term progressed, the interval between the first and second playings of “Black Dog” got shorter and shorter. And so we had to get up, get ready, and get out faster and faster. Rising before reveille was strictly verboten — prowling barmen assured adherence to that rule. In the final week, the disquieting track was played twice without pause, giving us just twice the four minute and fifty-six second duration of that malevolent melody to perform our morning ablutions, dress, square off the cabin, race down the central staircase of Nixon Block and out the main entrance. Memories of those morning scrambles are not among those that I look back on with nostalgia. For years afterwards, the ominous sound of Jimmy Page “waking up the army of guitars” followed by Robert Plant launching a cappella into “hey, hey, mama said the way you move” was guaranteed to make my pulse race, my breathing quicken, and a feeling of dread rise from the primitive part of my brain. But the happy part about behavioural conditioning, both operant and Pavlovian, is that without periodic reinforcement, such conditioning tends to be extinguished. In other words, as John Cleese so famously said in the film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, “I got better.” https://youtu.be/J6pZuAJjBa4

Postscript: For those who would like to re-experience the frisson of those early mornings of recruit term, have a listen here: